Fotóművészet

A 6 page publication in the Hungarian Photoart Magazine “Fotóművészet” in 2018, with the wonderful text by Andrea Bordács art historian.

The text in English:

Andrea Bordács:

Slow Life – The Photography of Csilla Szabó

In Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes discusses figurative images, stating that photography itself is basically the field of decay and nostalgia for the past and times gone by, depicting something real, something which has happened. For this reason, without even talking about documentation, it is authentic, and therefore as opposed to language, it authenticates itself. “Photography is not (or not necessarily) talking about what does not exist anymore, but about something that certainly existed at some point. This small difference is crucial. No single photograph pushes our intellect to nostalgic remembrances (lots of photographs exist outside of subjective time), but every last photograph that has been taken proves that certainty, that the essence of photography is that it proves the existence of its subject.”

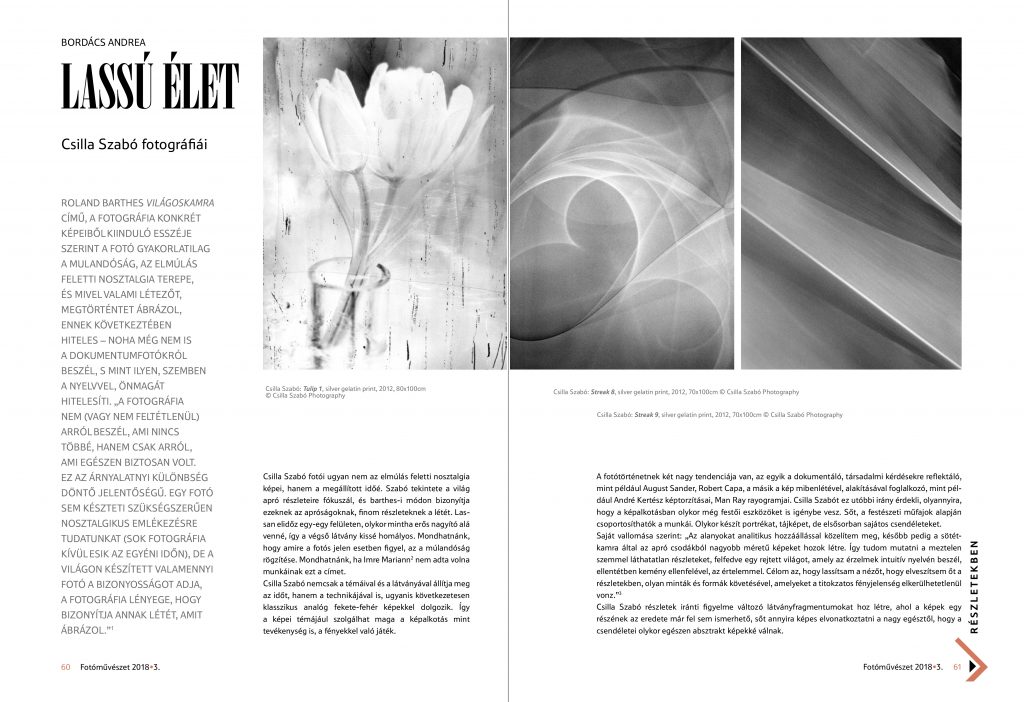

Csilla Szabó’s photographs are not pictures of nostalgia over passing time, but of time stopped. Szabó’s vision focuses on the tiny details of the world, and proves in Barthes’ way, the bare existence of these small, elegant details. She slowly takes her time on surfaces, sometimes it is as if she is holding them under such a strong magnifying glass that the final look is somewhat blurry. One could say that what the photographer really focuses on is the recording of the decay. One could say, if Mariann Imre had not already given the same title to her works.

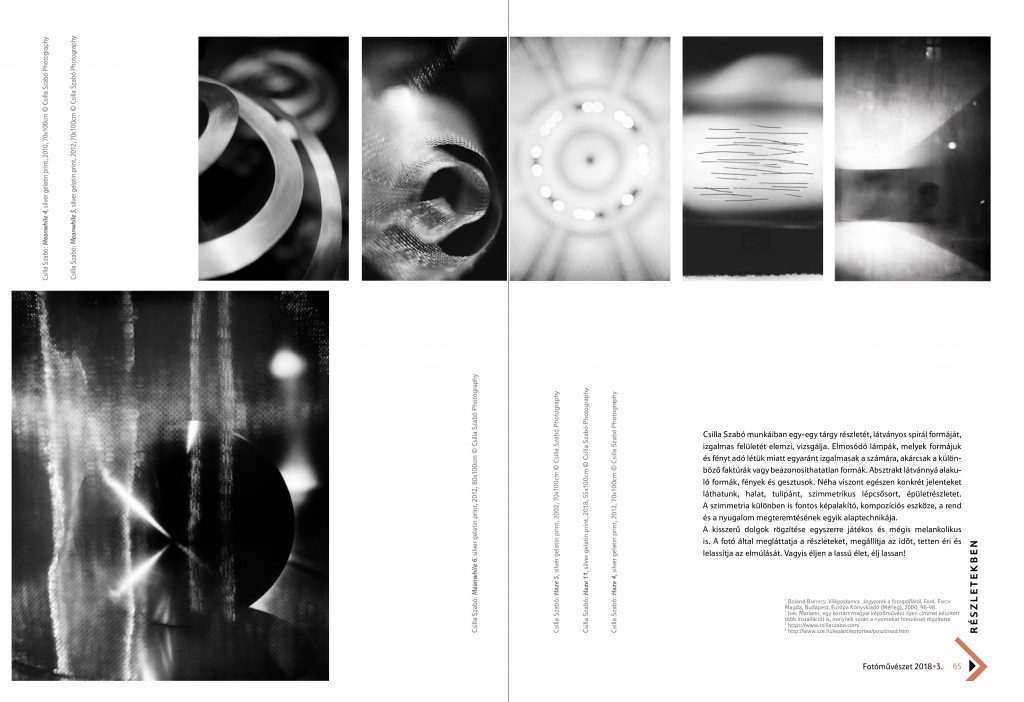

Csilla Szabó does not simply stop time with her subjects and way of picturing them, but also with her techniques too, using the medium of classical analog black and white photography. Even her way of capturing subjects can become the central theme with her playful use of light.

Photo history has two great tendencies: one in the documentarian sense; socio-reflective, like the works of August Sander and Robert Capa; the other focusing on the aesthetic of pictures, like the distortions of André Kertész or the rayograms of Man Ray. Csilla Szabó’s interest is the latter. Furthermore she uses aesthetics from painting; indeed her entire body of work can be distinguished in genres from painting: she depicts portraits, landscapes, but focuses mainly on unique still lifes.

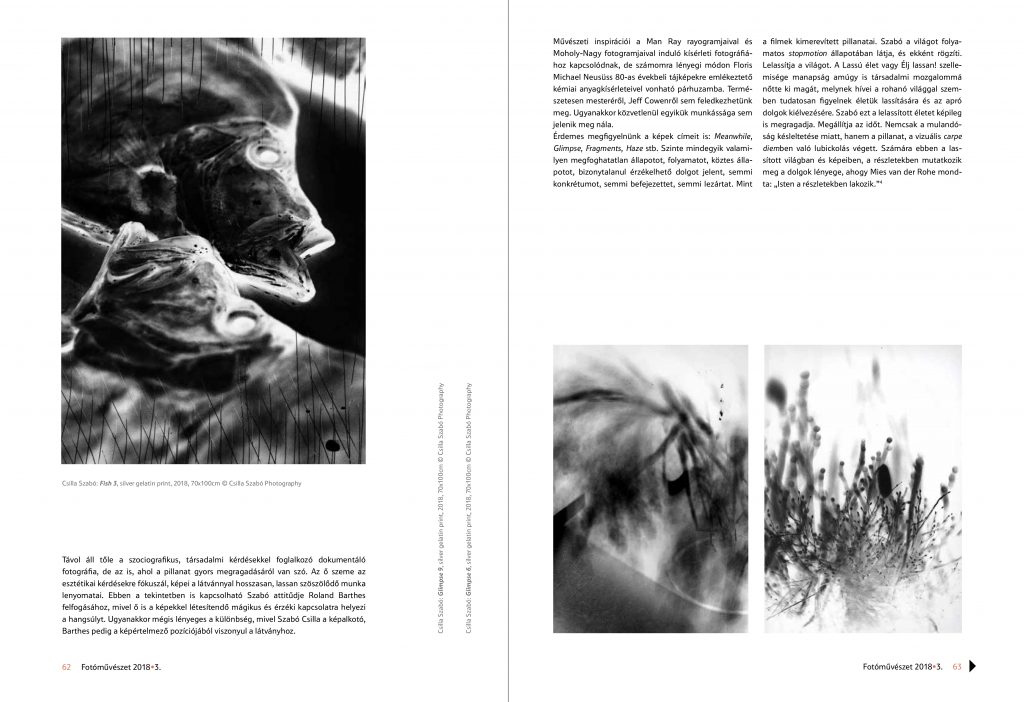

In her own words: “I approach my subjects with an analytic attitude, creating larger-than-life-sized images of tiny wonders in the darkroom. In this way I am able to showcase the minute details invisible to the naked eye, revealing a hidden world that speaks in the intuitive language of emotion, unlike its hardened opponent, the intellect. My intention is to slow down the viewer, to get them lost in the details, by following patterns and forms that the mysterious phenomenon of light inevitably draws.”

Csilla Szabó’s attention to detail creates different visual fragments, where parts of the original subjects cannot be recognized anymore, sometimes completely transforming her still lifes into abstract pieces.

Szabó is not interested in documentary photography, which focuses on social questions; neither is she interested in the kind of images which are solely about capturing a moment. Her eyes focus on the aesthetic; her pictures are the imprints of an extended, detailed finessing of visual elements. Her attitude can be connected to Roland Barthes’ in this regard as well, as she too lays the stress on a magical and sensual relationship with pictures. At the same time, there is an important difference, as while Csilla Szabó relates to the scene from the position of creation, Barthes does so from an explanatory position.

Her artistic inspirations connect to the early experimental photography like the rayograms of Man Ray and the photograms of Moholy-Nagy, but for me they line up closer to the chemical experiments of Floris Michael Neususs from the 80s, which remind the viewer of landscapes. Naturally we cannot overlook the influence of her mentor, Jeff Cowen either, but at the same time, none of these photographers’ work appear directly in hers.

It is interesting to look at her titles too: Meanwhile, Glimpse, Fragments, Haze, etc. Almost all are something ungraspable state, a continuance, an in-between-state, things that can be sensed with uncertainty, nothing is concrete, nothing is done, nothing is finished. Like the frozen pictures of a movie. Szabó sees the world in a continuous stop-motion state, and records it as such. She slows down the world. The idea of Slow Life or Living Slow has grown into a social movement, where as opposed to the rushing, fast world, they focus on slowing down life, and enjoying the small things. Szabo grabs this slowed life photographically. She stops time. Not only to stop decay, but for bathing in the visual carpe diem of the moment. For her, the true essence of things shows up in this slow, subjective world. As Mies van der Rohe said, “God lives in the details”.

While photographing, she analyzes and examines her subjects’ details, exciting forms, and interesting surfaces. Washed out lamps interest her for their light-giving attributes and the different factures and indescribable forms they produce. In her work shapes, lights, and gestures turn into an abstract vision. Sometimes we can also see concrete subjects: fish, a tulip, a symmetrical staircase, and building-details. Symmetry is also one of the foundational techniques she uses, creating by composition, balancing order and stillness.

The depiction of tiny things in Szabó’s work is playful and yet melancholic. Through her photography she showcases details, stopping time, capturing and slowing down decay. So, long live the slow life: live slow!